- BioVector NTCC典型培养物保藏中心

- 联系人:Dr.Xu, Biovector NTCC Inc.

电话:400-800-2947 工作QQ:1843439339 (微信同号)

邮件:Biovector@163.com

手机:18901268599

地址:北京

- 已注册

研究一个基因的功能,最常规的方法便是过表达(over-expression)和静默(knock-down或者knock-out),一般是通过外源基因转染宿主,进而观察宿主相关的表型(Phenotype)发生的变化(凋亡、增殖、周期、侵袭、迁移、上下游信号通路、EMT等等)来判断基因的功能。

不管是过表达还是静默,细胞水平的研究往往是选择构建稳定细胞株,研究细胞发生的变化。常规的构建稳定细胞株的方法有真核质粒转染、慢病毒包装。慢病毒包装周期较长,费用较高,对实验室硬件条件要求高,极大地限制了他的应用;普通的真核质粒转染周期较长,目的基因整合随机,对宿主要求高等缺点也限制其应用。随着新技术的不断革新,针对真核质粒转染构建稳定细胞株的方法也不断的创新,出现TALEN、IOS、Cas9、Flp-In等技术,不断地提高稳定细胞株构建的成功率。

尤其是Flp-In系统,以其独特的优点,迅速被各大实验室采用,近些年累计发表的文献越来越多,得到广大科研工作者的认可。

Flp-In™ System总览:

Flp-In™完整系统(Flp-In™ Complete System)可使目的基因在哺乳动物细胞基因组的特定位点整合和表达。Flp-In系统(Flp-In System)涉及将Flp重组靶(FRT)位点导入所选哺乳动物细胞系的基因组中。然后通过Flp重组酶介导在FRT位点的DNA重组,将含有目的基因的表达载体整合到基因组中。

Flp-In™系统(Flp-In™ System)的主要组分包括:

1. Flp-In靶位点载体pFRT⁄lacZeo,用于制备含有FRT整合位点的宿主细胞系

2. 含有与潮霉素抗性基因相连的FRT位点的表达质粒,用于在Flp重组酶介导下,整合和筛选表达目的基因的稳定细胞系;目的基因的表达由人巨细胞病毒(CMV)即刻早期增强子⁄启动子调控

3. Flp重组酶表达质粒pOG44,用于在人CMV启动子调控下表达Flp重组酶

4. 含有氯霉素乙酰基转移酶(CAT)基因的对照表达质粒,在与pOG44共转染到Flp-In宿主细胞系中时表达CAT

Flp-In™ System的优点:

1. 一旦成功构建含FRT整合位点的Flp-In母细胞株,接下来构建表达目的基因稳定细胞株的工作就快速、高效;

2. Flp-In系统能构建同基因型的稳定细胞株;

3. Flp-In系统可以是多克隆稳定细胞株,无需纯化。

Flp-In™ System描述:

Flp-In系统依据酿酒酵母的DNA重组系统的特点,高效构建稳定哺乳动物表达细胞株。这种DNA重组系统应用重组酶(Flp)和定点重组技术(Craig, 1988; Sauer, 1994),将目的基因插入到哺乳动物指定的基因组中。

Flp-In系统运用3种不同的质粒来构建同基因型的稳定细胞株。

pFRT/lacZeo质粒是用来构建Flp-In母细胞株。质粒包含lacZ-Zeocin融合基因,有SV40早期启动子控制表达。FRT位点被插入在lacZ-Zeocin融合基因的ATG起始密码子下游。FRT位点是用来与Flp重组酶结合,进而被剪切。pFRT/lacZeo转染进细胞中,然后通过Zeocin抗生素筛选细胞,阳性克隆细胞即含单一的FRT整合位点。Flp-In母细胞株含FRT位点和表达lacZ-Zeocin融合基因。pFRT/lacZeo质粒整合进入基因组是随机的。

第二个主要的质粒是pcDNA5/FRT表达载体,用来将目的基因克隆进去,目的基因由hCMV启动子控制,载体还有Hygromycin抗体基因,还有5’编码区的FRT位点。Hygromycin抗性基因缺少启动子和ATG起始密码子。

第三个主要的质粒是pOG44载体,用来表达Flp重组酶(Broach et al., 1982; Broach and Hicks, 1980; Buchholz et al., 1996),由hCMV启动子控制。

pOG44质粒和含目的基因的pcDNA5/FRT质粒共转Flp-In母细胞株,Flp重组酶介导FRT位点的同源重组(母细胞基因组和pcDNA5/FRT),这样pcDNA5/FRT的目的基因插入基因组。同时将Hygromycin抗性基因插入到pFRT/lacZeo的SV40启动子和ATG起始密码子下,抑制了lacZ-Zeocin融合基因的表达。这样的话Flp-In稳定细胞株就可以通过hygromycin耐受、Zeoncin敏感、缺少ß-半乳糖苷酶活性、表达目的基因4个特性去筛选得到。

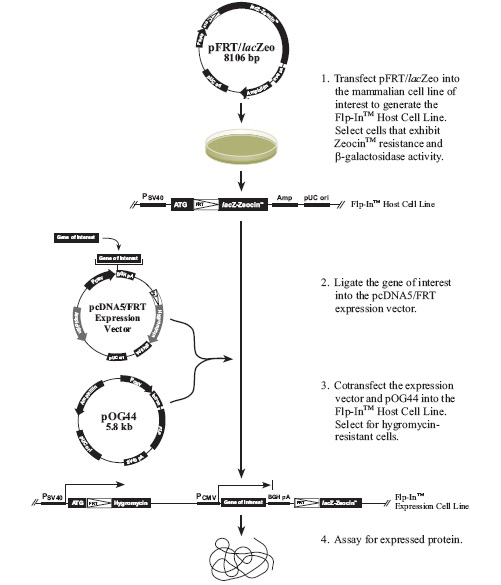

Flp-In™ System流程图:

下图描述了Flp-In系统的主要流程:

Flp重组酶介导DNA的重组:

在Flp-In系统中,Flp重组酶介导分子间的DNA重组,Flp重组酶介导的重组有如下特点:

1. 重组发生在特异的FRT位点;

2. 重组很保守,不需要DNA合成,FRT重组位点被保护,使重组位点发生突变的可能性降到最低;

3. 重组仅仅需要34bpFRT位点。

更多关于Flp重组酶和保守位点特异重组请参考文献(Craig, 1988; Sauer, 1994).

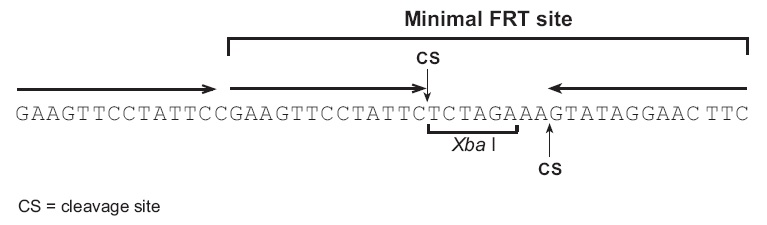

FRT位点:

FRT位点最初从酿酒酵母中分离得到,并被深入研究(Gronostajski and Sadowski, 1985; Jayaram, 1985; Sauer, 1994; Senecoff et al., 1985).最短的FRT位点包含34bp序列,包含2个13bp的片段序列,中间8bp序列含Xba I限制性酶切位点,另外13bp重复序列在大多数FRT位点中也有,但是并不是剪切所必须的(Andrews et al., 1985).当Flp重组酶结合到3段13bp的序列上时,剪切发生在中间的8bp区域(Andrews et al., 1985; Senecoff et al., 1985).

实验流程:

将pFRT/lacZeo质粒转染细胞,构建Flp-In母细胞株;

将目的基因克隆进pcDNA5/FRT表达载体;

在Flp-In母细胞中共转pcDNA5/FRT和pOG44质粒,构建出Flp-In表达细胞株;

检测目的基因的表达。

Flp-In™母细胞株构建:

BioVector NTCC Inc.从Invitrogen公司购得Flp-In™-293、Flp-In™-CV-1、Flp-In™-CHO、Flp-In™-BHK、Flp-In™-3T3、Flp-In™-Jurkat,节约客户的时间,同时也提供其他细胞上的的Flp-In母细胞株构建服务。

Cell Line | Source | Catalog no. |

Flp-In™-293 | Human embryonic kidney | NTCC600101 |

Flp-In™-CV-1 | African Green Monkey kidney | NTCC600102 |

Flp-In™-CHO | Chinese Hamster ovary | NTCC600103 |

Flp-In™-BHK | Baby hamster kidney | NTCC600104 |

Flp-In™-3T3 | Mouse (NIH Swiss) embryonic fibroblast | NTCC600105 |

Flp-In™-Jurkat | Human T-cell leukemia | NTCC600106 |

案例展示:

| |

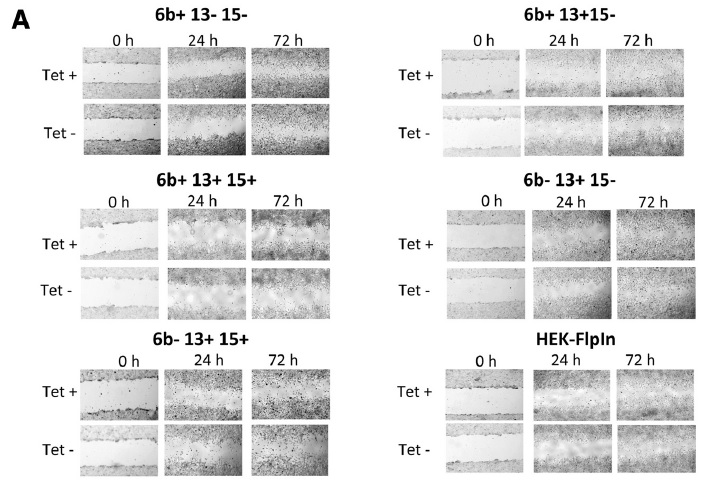

| Figure 4 Cell migration and proliferation assay of TMEM16A variants.A, Representative images of wound healing in a scratch assay with inducible expression of TMEM16A variants in HEK293 cells cultured with (Tet+) or without (Tet?) tetracycline (0.1 μg/ml). Original magnification, 4x. (Scale bars: 5 μm). B, Quantification of the fraction of the wound that remains uncovered by the migratory cells as a function of time for cell treated with (Tet+) or without (Tet?). C, Cellular proliferation assay, BrdU staining of cells expressing TMEM16A variants (treated without or with tetracycline). Data represent the % of BrdU+ cells and are the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. | |

All the coding sequences for TMEM16A were cloned in the pcDNA5 FRT/TO plasmid. Stable expression of TMEM16A variants was achieved by Flp-recombinase-mediated recombination in HEK293 Flp-In cells followed by hygromycin B selection. Each TMEM16A-expressing vector that expresses the Flp-recombinase was cotransfected with Effectene transfection reagent and selected with a concentration of 200μg/ml hygromycin B. Individual clones were obtained by limited dilution. Induction of TMEM16A isoforms expression was achieved with 0.1μg/ml tetracycline . Cells were grown in DMEM-Glutamax-I media supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum. | |

| 标题: | TMEM16A alternative splicing coordination in breast cancer |

| 杂志: | Molecular Cancer |

| 作者: | Ifeoma Ubby, Erica Bussani, Antonio Colonna, Giuseppe Stacul, Martina Locatelli, Paolo Scudieri, Luis Galietta and Franco Pagani |

| |

Figure 3. Inducible expression of hSLCO5A1 in HeLa cells. Protein expression of the YFP-tagged WT SLCO5A1 or its L33F mutant after induction with 1 mg/ml tetracycline for 24 h was analyzed by confocal fluorescence microscopy (blue: DAPI; yellow: YFP). The diagrams represent YFP fluorescence intensities along the length of the red arrows (x-axis: distance [μm]; y-axis: relative signal intensity). | |

Flp-In T-REx-HeLa cells allow the tetracycline-inducible expression of a gene of interest from a specific genomic location. Stable SLCO5A1-expressing Flp-In TREx-HeLa cells were generated using the FlpIn recombinasemediated system kit, which permits the targeted integration of genes to the same locus in all transfected cells to provide a homogeneous level of gene expression. To this end, cells were co-transfected with the FlpIn expression vector pcDNA5/FRT/TO (mock) or with the same vector containing the wild-type (WT) or mutant (L33F) sequence for SLCO5A1, modified C-terminally with either the sequence for a HA epitope or a YFP-tag or left unmodified, together with the Flp-recombinase expression vector pOG44. Individual clones were separated by monoclonal selection with 15 mg/ml blasticidin and 100 mg/ml hygromycinB. Cells were cultured in EMEM supplemented with 10% FCS (tetracycline/doxycycline-reduced). SLCO5A1-expression was induced by adding 1 mg/ml tetracycline (tet) to the Flp-In TREx-HeLa cells (hereinafter referred to as HeLa cells). | |

| 标题: | Characterization of SLCO5A1/OATP5A1, a Solute Carrier Transport Protein with Non-Classical Function |

| 杂志: | PLOS ONE |

| 作者: | Katrin Sebastian, Silvia Detro-Dassen, Natalie Rinis, Dirk Fahrenkamp, Gerhard Mu¨ller-Newen, Hans F. Merk, Gu¨ nther Schmalzing, Gabriele Zwadlo-Klarwasser, Jens Malte Baron |

| |

Fig.1. PEX14–TEV–Protein A localizes to peroxisomes and is functional. Validation of the peroxisomal localization of the Protein-A-tagged genomic copy of PEX14. Cell lines Flp-In-293 cells and Flp-In-293 [PEX14–TEV– Protein A] were transiently transfected with a plasmid encoding the peroxisomal marker EGFP–PTS1. Specific immunodetection of the fusion protein PEX14–TEV–Protein A was carried out with anti-Protein A antibodies, the endogenous and the fusion protein were detected by using antibodies against PEX14. Scale bars:10 um. | |

Generation and selection of stable cell lines expressing PEX14–TEV–ProteinA | |

| 标题: | PEX14 is required for microtubule-based peroxisome motility in human cells |

| 杂志: | Journal of Cell Science |

| 作者: | Pratima Bharti, Wolfgang Schliebs, Tanja Schievelbusch, Alexander Neuhaus, Christine David, Klaus Kock, Christian Herrmann, Helmut E. Meyer, Sebastian Wiese, Bettina Warscheid, Carsten Theissand Ralf Erdmann |

| |

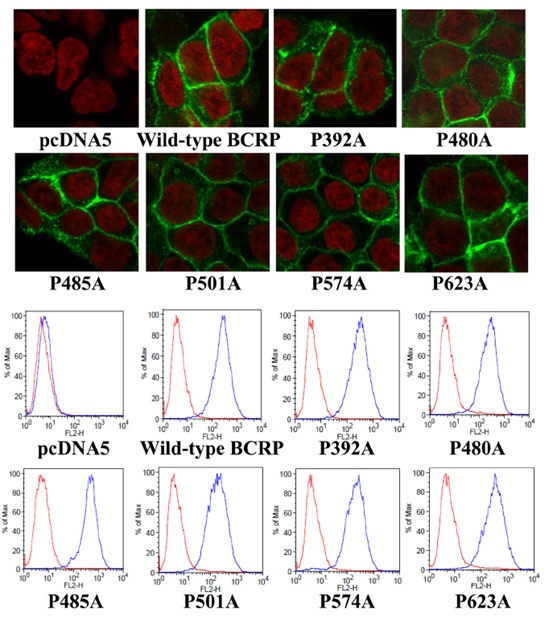

Figure 3. Confocal microscopy analysis and cell surface expression of Flp-In™-293 cells stablyexpressing wild-type and mutant BCRP. A) The cellular localization of wild-type and mutant BCRP in Flp-In™-293 cells (shown ingreen) was determined by immunofluorescent confocal microscopy using the BCRP-specific mAb BXP-21. Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI and are shown in red. B) Expression of wild-type and mutant BCRP on cell surface of stably transfected Flp-In™-293 cells was detected using the 5D3 monoclonal antibody. Representative flow cytometry histograms | |

Generation of Flp-In™-293 cells stably expressing wild-type BCRP and proline mutants | |

| 标题: | Identification of Proline Residues In or Near the Transmembrane Helices of the Human Breast Cancer Resistance Protein (BCRP/ABCG2) Important for Transport Activity and Substrate Specificity |

| 杂志: | Biochemistry |

| 作者: | Zhanglin Ni, Zsolt Bikadi, Diana L. Shuster, Chunsheng Zhao, Mark F. Rosenberg, and Qingcheng Mao |

参考文献:

1. Andersson, S., Davis, D. L., Dahlbäck, H., Jörnvall, H., and Russell, D. W. (1989). Cloning, Structure, and Expression of the Mitochondrial Cytochrome P-450 Sterol 26-Hydroxylase, a Bile Acid Biosynthetic Enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 264, 8222-8229.

2. Andrews, B. J., Proteau, G. A., Beatty, L. G., and Sadowski, P. D. (1985). The FLP Recombinase of the 2 Micron Circle DNA of Yeast: Interaction with its Target Sequences. Cell 40, 795-803.

3. Argos, P., Landy, A., Abremski, K., Egan, J. B., Ljungquist, E. H., Hoess, R. H., Kahn, M. L., Kalionis, B., Narayana, S. V. L., and Pierson, L. S. (1986). The Integrase Family of Site-Specific Recombinases: Regional Similarities and Global Diversity. EMBO J. 5, 433-440.

4. Ausubel, F. M., Brent, R., Kingston, R. E., Moore, D. D., Seidman, J. G., Smith, J. A., and Struhl, K. (1994). Current Protocols in Molecular Biology (New York: Greene Publishing Associates and Wiley-Interscience).

5. Baron, M., Reynes, J. P., Stassi, D., and Tiraby, G. (1992). A Selectable Bifunctional b-Galactosidase: Phleomycin-resistance Fusion Protein as a Potential Marker for Eukaryotic Cells. Gene 114, 239-243.

6. Boshart, M., Weber, F., Jahn, G., Dorsch-Häsler, K., Fleckenstein, B., and Schaffner, W. (1985). A Very Strong Enhancer is Located Upstream of an Immediate Early Gene of Human Cytomegalovirus. Cell 41, 521-530.

7. Broach, J. R., Guarascio, V. R., and Jayaram, M. (1982). Recombination Within the Yeast Plasmid 2mu Circle is Site-specific. Cell 29, 227-234.

8. Broach, J. R., and Hicks, J. B. (1980). Replication and Recombination Functions Associated with the Yeast Plasmid, 2 mu Circle. Cell 21, 501-508.

9. Buchholz, F., Ringrose, L., Angrand, P. O., Rossi, F., and Stewart, A. F. (1996). Different Thermostabilities of FLP and Cre Recombinases: Implications for Applied Site-specific Recombination. Nuc. Acids Res. 24, 4256-4262.

10. Calmels, T., Parriche, M., Burand, H., and Tiraby, G. (1991). High Efficiency Transformation of Tolypocladium geodes Conidiospores to Phleomycin Resistance. Curr. Genet. 20, 309-314.

11. Chen, C., and Okayama, H. (1987). High-Efficiency Transformation of Mammalian Cells by Plasmid DNA. Mol. Cell. Biol. 7, 2745-2752.

12. Chu, G., Hayakawa, H., and Berg, P. (1987). Electroporation for the Efficient Transfection of Mammalian Cells with DNA. Nuc. Acids Res. 15, 1311-1326.

13. Craig, N. L. (1988). The Mechanism of Conservative Site-Specific Recombination. Ann. Rev. Genet. 22, 77-105.

14. Drocourt, D., Calmels, T. P. G., Reynes, J. P., Baron, M., and Tiraby, G. (1990). Cassettes of the Streptoalloteichus hindustanus ble Gene for Transformation of Lower and Higher Eukaryotes to Phleomycin Resistance. Nuc. Acids Res. 18, 4009.

15. Felgner, P. L., Holm, M., and Chan, H. (1989). Cationic Liposome Mediated Transfection. Proc. West. Pharmacol. Soc. 32, 115-121.

16. Felgner, P. L., and Ringold, G. M. (1989). Cationic Liposome-Mediated Transfection. Nature 337, 387-388.

17. Graham, F. L., Smiley, J., Russell, W. C., and Nairn, R. (1977). Characteristics of a Human Cell Line Transformed by DNA from Human Adenovirus Type 5. J. Gen. Virol. 36, 59-74.

18. Gritz, L., and Davies, J. (1983). Plasmid-Encoded Hygromycin-B Resistance: The Sequence of Hygromycin-B-Phosphotransferase Gene and its Expression in E. coli and S. cerevisiae. Gene 25, 179-188.

19. Gronostajski, R. M., and Sadowski, P. D. (1985). Determination of DNA Sequences Essential for FLP-mediated Recombination by a Novel Method. J. Biol. Chem. 260, 12320-12327.

20. Huang, M. T. F., and Gorman, C. M. (1990). Intervening Sequences Increase Efficiency of RNA 3′ Processing and Accumulation of Cytoplasmic RNA. Nuc. Acids Res. 18, 937-947.

21. Jainchill, J. L., Aaronson, S. A., and Todaro, G. J. (1969). Murine Sarcoma and Leukemia Viruses: Assay Using Clonal Lines of Contact-Inhibited Mouse Cells. J. Virol. 4, 549-553.

22. Jayaram, M. (1985). Two-micrometer Circle Site-specific Recombination: The Minimal Substrate and the Possible Role of Flanking Sequences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 82, 5875-5879.

23. Kao, F. T., and Puck, T. T. (1968). Genetics of Somatic Mammalian Cells, VII. Induction and Isolation of Nutritional Mutants in Chinese Hamster Cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 60, 1275-1281.

24. Kit, S., Dubbs, D. R., DeTorres, R. A., and Melnick, J. L. (1965). Enhanced Thymidine Kinase Activity Following Infection of Green Monkey Kidney Cells by Simian Adenoviruses, Simian Papovavirus SV40, and an Adenovirus-SV40 "Hybrid". Virology 27, 453-457.

25. Miller, J. H. (1972). Experiments in Molecular Genetics (Cold Spring Harbor, New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory).

26. Mulsant, P., Tiraby, G., Kallerhoff, J., and Perret, J. (1988). Phleomycin Resistance as a Dominant Selectable Marker in CHO Cells. Somat. Cell Mol. Genet. 14, 243-252.

27. Nelson, J. A., Reynolds-Kohler, C., and Smith, B. A. (1987). Negative and Positive Regulation by a Short Segment in the 5′-Flanking Region of the Human Cytomegalovirus Major Immediate-Early Gene. Mol. Cell. Biol. 7, 4125-4129.

28. Neumann, J. R., Morency, C. A., and Russian, K. O. (1987). A Novel Rapid Assay for Chloramphenicol Acetyltransferase Gene Expression. BioTechniques 5, 444-447.

29. O'Gorman, S., Fox, D. T., and Wahl, G. M. (1991). Recombinase-Mediated Gene Activation and Site-Specific Integration in Mammalian Cells. Science 251, 1351-1355.

30. Palmer, T. D., Hock, R. A., Osborne, W. R. A., and Miller, A. D. (1987). Efficient Retrovirus-Mediated Transfer and Expression of a Human Adenosine Deaminase Gene in Diploid Skin Fibroblasts from an Adenosine-Deficient Human. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 84, 1055-1059.

31. Perez, P., Tiraby, G., Kallerhoff, J., and Perret, J. (1989). Phleomycin Resistance as a Dominant Selectable Marker for Plant Cell Transformation. Plant Mol. Biol. 13, 365-373.

32. Sambrook, J., Fritsch, E. F., and Maniatis, T. (1989). Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, Second Edition (Plainview, New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press).

33. Sauer, B. (1994). Site-Specific Recombination: Developments and Applications. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 5, 521-527.

34. Senecoff, J. F., Bruckner, R. C., and Cox, M. M. (1985). The FLP Recombinase of the Yeast 2-micron Plasmid: Characterization of its Recombination Site. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 82, 7270-7274.

35. Shigekawa, K., and Dower, W. J. (1988). Electroporation of Eukaryotes and Prokaryotes: A General Approach to the Introduction of Macromolecules into Cells. BioTechniques 6, 742-751.

36. Talavera, A., and Basilico, C. (1977). Temperature Sensitive Mutants of BHK Cells Affected in Cell Cycle Progression. J. Cell. Physiol. 92, 425-436.

37. Wigler, M., Silverstein, S., Lee, L.-S., Pellicer, A., Cheng, Y.-C., and Axel, R. (1977). Transfer of Purified Herpes Virus Thymidine Kinase Gene to Cultured Mouse Cells. Cell 11, 223-232.

您正在向 biovector.net 发送关于产品 Flp-in system稳定表达细胞株构建方法- FLP重组酶介导的基因整合 的询问

- 公告/新闻